The streets of Lambeth, in the shadow of the Palace of Westminster just over the River Thames, were once among the most impoverished in London, but are now filled with shiny new-build apartment blocks and lavishly-restored Georgian homes.

But hidden among the gentrification remains a rugged jewel in the crown, Fitzroy Lodge Amateur Boxing Club. It has been a hotbox of blood, toil, sweat and tears for more than a century — and the fundamental life lessons taught here are now more important than ever.

Since opening its doors in 1910, the coaches at Fitzroy Lodge have trained world boxing champions including Cornelius Boza-Edwards and David Haye. But their work with members who are not household names is an even prouder achievement, helping thousands of disadvantaged youngsters and ex-offenders to find purpose in their lives.

Fitzroy Lodge ABC // 📸: Hamish Brown

“I was one of them naughty kids that always got into trouble. Ducking and diving. I’ve done a lot of things that I’d never tell my mum,” says the gym’s head coach Mark Reigate, 47.

“But the one thing I really enjoyed was sport. So I started going boxing, I thought I could look after myself and I was a tough little nut. And on the first day, I jumped in the ring with this fella and my first reaction was to hit him as hard as I could, and I thought, ‘This is easy.’

“Then he looked at me and gave me a good hiding. I couldn’t believe how easy it was for him. And then I was hooked. I started coming down to Fitzroy Lodge at the age of 19, and have been here ever since.

“Boxing has taught me to respect anybody, whoever is put in front of me. It’s taught me self control, routine and structure. And it has taught me how to win and lose, then get back up and carry on.”

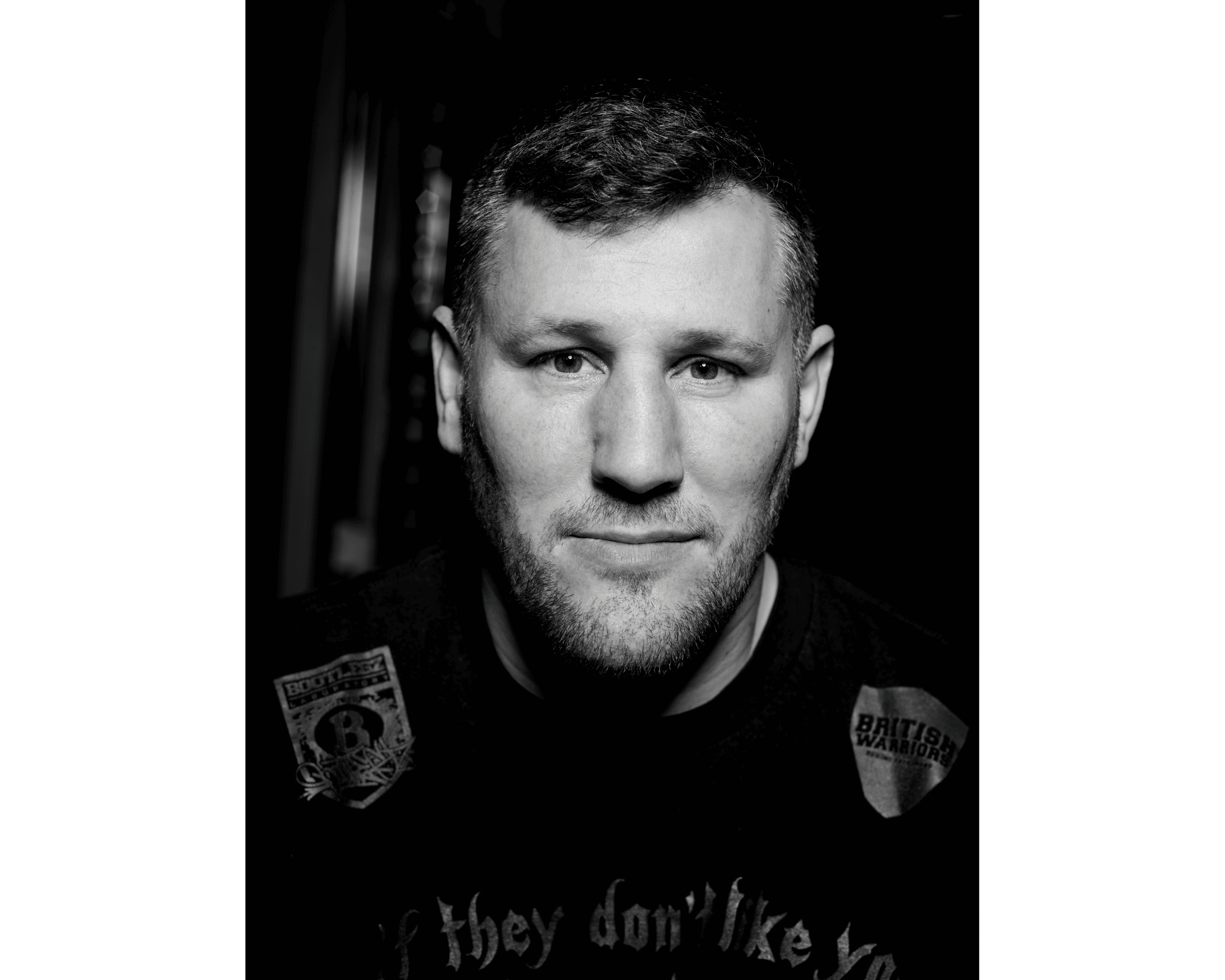

Fitzroy Lodge trainer Linton Aymer // 📸: Hamish Brown

On the surface, boxing is about one man hurting another. But under the bruised and bloodied exterior it can help the fighters find out who they are inside, and even heal. Boxing has long been a refuge for young people seeking to control their aggression. And once you find self-confidence in the ring, there is less need to prove yourself on the streets.

Fitzroy Lodge has a long-standing reputation of teaching the honorable side of this violent sport. Boxing legend Mick Carney ran the place until his death in 2011, and was honored with an MBE by the Queen for turning around so many lives. And following his death, Mark co-founded Carney’s Community with friend George Turner in his honor, a non-profit to help guide local youths impacted by crime and violence to realize their potential.

Mark, who grew up in Shirley, south London, boxed until he was 33, competing in 102 fights and winning the South East London title three times, before his mentor Mick offered him the path to become a coach himself, and pass on the wisdom he had learned to the next generation.

Mentoring is at the heart of the work done here. Carney’s Community use the facilities in the day, offering guidance to youngsters who have fallen into crime, and by night the more serious boxers come to train — many of whom have graduated from Mark’s youth charity initiative, and are continuing on their path of self-improvement, while becoming mentors themselves.

Mark sparring with a young member // 📸: Hamish Brown

Mark explains, “At Carney’s Community we work with young offenders and help the well-being of young people. The boxing gets them involved, and we keep them out of trouble and help them get work. I mentor kids, who go on to mentor younger kids, and it goes on like that.

“Some of them haven’t got dads. Me and my brother, our dad used to float in and out of our lives, my mum was the one who brought us up. It was all my coaches that mentored me, and the final one was Mick.

“Mick was very high up in boxing, amateur and professional, everybody knew him and respected him. A lot of the old-time gangsters like the Krays and the Richardsons, that everyone looked up to, they all knew Mick and gave him a lot of respect, without him needing to be a gangster.

“Mick had a lot of class and he knew how to talk to people. I learned a lot from him about how to present yourself, and that you don’t need to be a bully to be heard. If you treat everyone with respect then everyone will respect you. And if you don’t like someone, don’t bother with them. I try to pass that on.

“Sometimes when I hear what these kids have got going on it makes me think how lucky I am. I thought I wasn’t brought up properly. We had no money and my dad was in and out of prison. But some of these kids were brought up totally different to me, and I sit there and think, ‘F****** hell.’

“Boxing teaches structure. I tell the kids if you can get up and go for a run, you can get up and go to work. They all want to come in and be world champions, but we tell them they need to have two things, learn another skill and have boxing as a hobby, and if boxing doesn’t pay off then you have something else.”

Ede Omoregie // 📸: Hamish Brown

Some may question the logic of teaching youngsters already on the edges of crime how to fight. But the self-discipline and code of honor taught at Fitzroy Lodge has benefits far outside the ring.

One of the young men who Mark has mentored is Ede Omoregie, 28, who first walked into the gym ten years ago after being involved in a robbery and landing himself in trouble with the law. He did not have any GCSEs, the first qualification most Brits achieve at age 16, but now, a decade later, he has a degree in business from the University of Manchester and is on the verge of turning pro as a boxer.

“When I was young I was very stubborn and hard-headed, and when I started boxing I thought I could adopt that same mentality,” Ede explains.

“I thought I could just come in here and do things my way, but boxing teaches you to listen and be humble. I learned that the hard way.

“You learn to deal with the ups and downs in life, be resilient and to bounce back and achieve your full potential. These principles of hard work can be applied in different aspects of your life. Everything you want to work for in life, you have put in your all. While I was studying it helped having this passion for boxing. It’s kind of a lonely sport, you get used to being on your own. So I just studied and boxed. And it gives you self-confidence knowing that you can do it.”

Fitzroy Lodge boxers (L-R) Aijay, Byron Robinson and Joey Ephson // 📸: Hamish Brown

Now Ede, from Stockwell, south west London, hopes he can pass on the wisdom he has learned to some of the younger men and women searching for more purpose in their lives.

He says: “A lot of youths are lost and don’t know who they are. So you see this knife crime and gun crime because they are creating a fake image of themselves. But in a boxing environment, it shows you who you truly are.

“I had both parents, I’m from a good family, but growing up in certain areas, you can be led astray. And now I get to a certain age, I feel like I can educate the youth and become a mentor. Because we don’t really have role models coming from where we come from, people who can relate to what we went through.

“Their role models are older people in their area, living the fast life and making money on the street. And they think that’s a way out. But I’m going to show them everyone has their own individual skills. We are all special in our own way. Some people don’t excel in academics, so they think they’re not good enough. But there are lots of different types of genius. There are people that are good at art, music, sport, so it’s directing people towards their own inner genius.”

Fitzroy Lodge boxer Ricco Oseiropp // 📸: Hamish Brown

Head coach Mark believes the community and support offered by his team is now more crucial than ever. Gun and knife crime was on the rise in London before the pandemic hit, with homicides in the city hitting a 10-year high in 2019.

Mark says, “Things are getting worse. When we were growing up on our estate we had a youth club and somewhere to go.

“So even though we were all being pains in the arse, at least we were in one place and being watched and supervised. But now the youth centers have gone — they’ve been sold off and turned into flats. Especially here in Lambeth, it’s all designer flats worth millions of pounds.

“And there was more of a community feeling. If my mum was out working there were other people looking out for us, feeding us and they would tell us off if we were misbehaving. And then they’d tell my mum, who would tell us off too.”

Fitzroy Lodge boxer Papa Anno // 📸: Hamish Brown

And now the health crisis and lockdown has posed a new challenge for keeping youths active and engaged.

“We’ve still been with the kids, it’s important,” Mark says. “We have little bubbles where we work with five kids and if one of you gets it you all have to isolate. Because there are lots of people who have tried to use it as an excuse not to do anything. But you have to keep them involved or they’re going to get bored, go out and get into trouble.

“We’ve got to keep an eye on them and make sure they are motivated, concentrating and still here.”

Fitzroy Lodge // 📸: Hamish Brown

Of course, your problems don’t disappear once you decide to put on the gloves and enter the ring. Linton Aymer, 40, first walked into Fitzroy Lodge in 2007 shortly after serving a five-year prison sentence for conspiracy to burgle. But he went back to jail in 2012, before returning to boxing after his release in 2016, and has now become a coach at the gym.

And he now uses his experiences to warn newcomers of the harsh reality of what can happen if you don’t learn tough lessons from your mistakes.

He says, “I tell them how it is, that I got stabbed five times and have been shot in the leg. And I say, ‘Whatever it is you’re doing, you need to stop, mate. Everything you’re doing, I’ve already done.’

“I’ll tell you what happens if you go to jail — you’re laying in bed and another guy is having a s*** by your head. They listen to me, and it makes me feel good inside.”

Mark and his brother Barry, an acclaimed artist // 📸: Hamish Brown

Learn more about Fitzroy Lodge at www.fitzroylodge.club and Carney’s Community on their Facebook page.